- July 13, 2022

- Khushi Nansi (M.S. in the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Art & Architecture '23)

Research Foreward - Investigating the Secret Capital: Oral Histories and Material Analysis of Women's Jewelry

Bombay Women of Mine

If ever something happens to me—my mother always begins this way—here is where the silver is kept. Did you hear me? Listen. I’ll tell you where to find the gold. But each time I am admonished: never sell it. Gold will only increase in value. Understood? She holds the guineas in her palm then slips them back into the velvet pouch. Close close close pack pack lock lock, slide the key click and close. All concealed. My childhood hinged on visits to the locker vault, pieces picked for different celebration. She spoke to me there as she inspected each set. Uncut diamonds and carats, sapphires and pearls, rubies and emeralds and gold, so much gold—I can recall vividly how they looked under the light of the adjoining room in the vault. At home she cleaned the silver trays for her fast, and told me where her silver lay in a now sold flat in Bombay/Mumbai. Such was the language of my mother, warning me of futures without her.

As a child I hated any adornment (aside from a brief ten-year old fascination for dangling smiling monkeys and paperclip earrings of the early 2010s). I wore gold studs under compulsion. To my many protests she said only: the holes will close. You will pierce them again? It will be painful. I was fearful, I gave in. I sat still as she slid the posts through my earlobes, petroleum jelly making the changes between earrings smoother. My ears would be red, inflamed, I would grow irritated until I forgot I wore them at all. Most often, I wore diamonds gifted by my brother before he died. Only as I grew older did I become curious about the vault, about the stories. And then, only because of the removal of certain pieces in my family did I feel the keen pain of a separation. I felt ousted, I no longer belonged to those I had once.

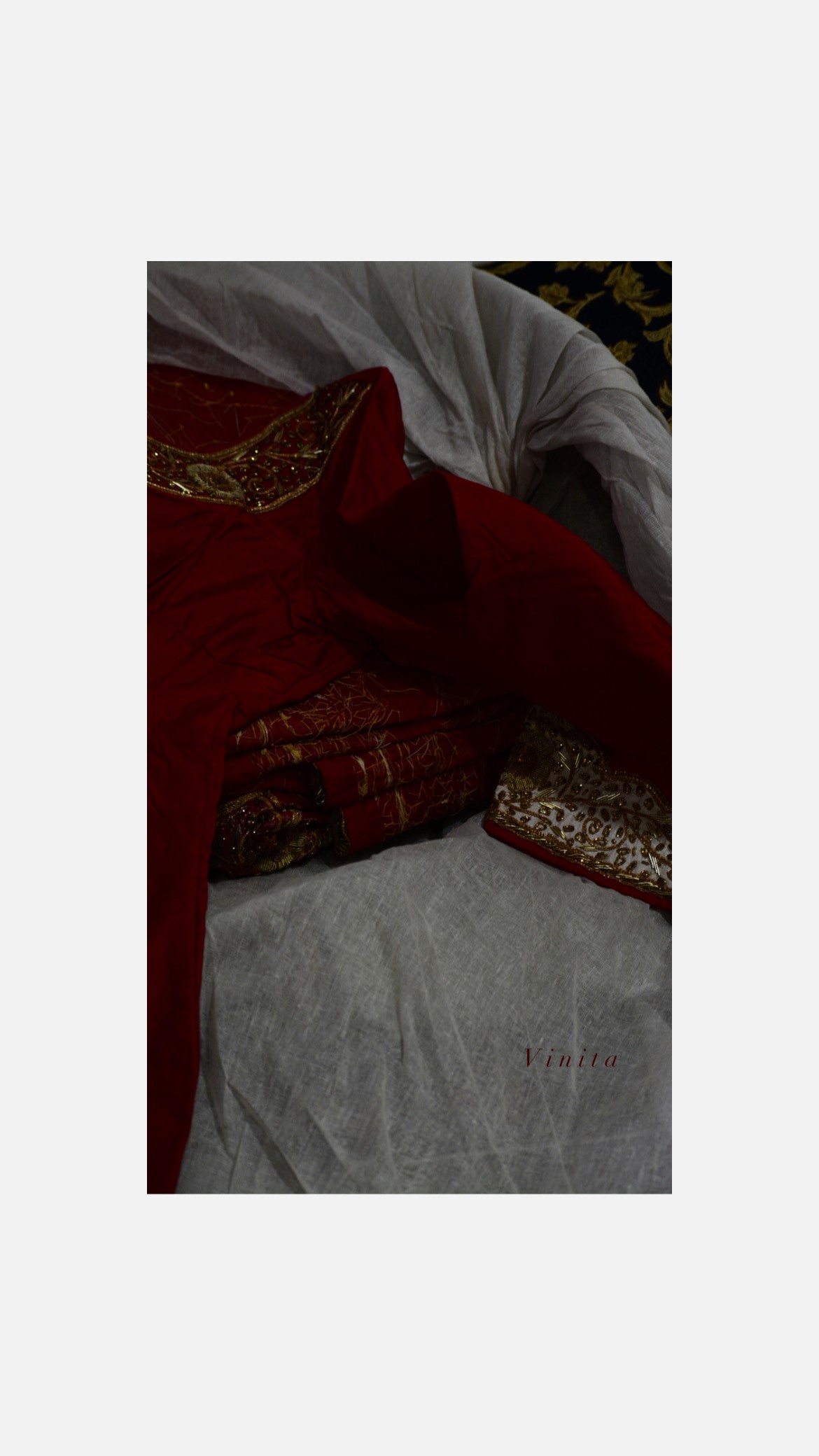

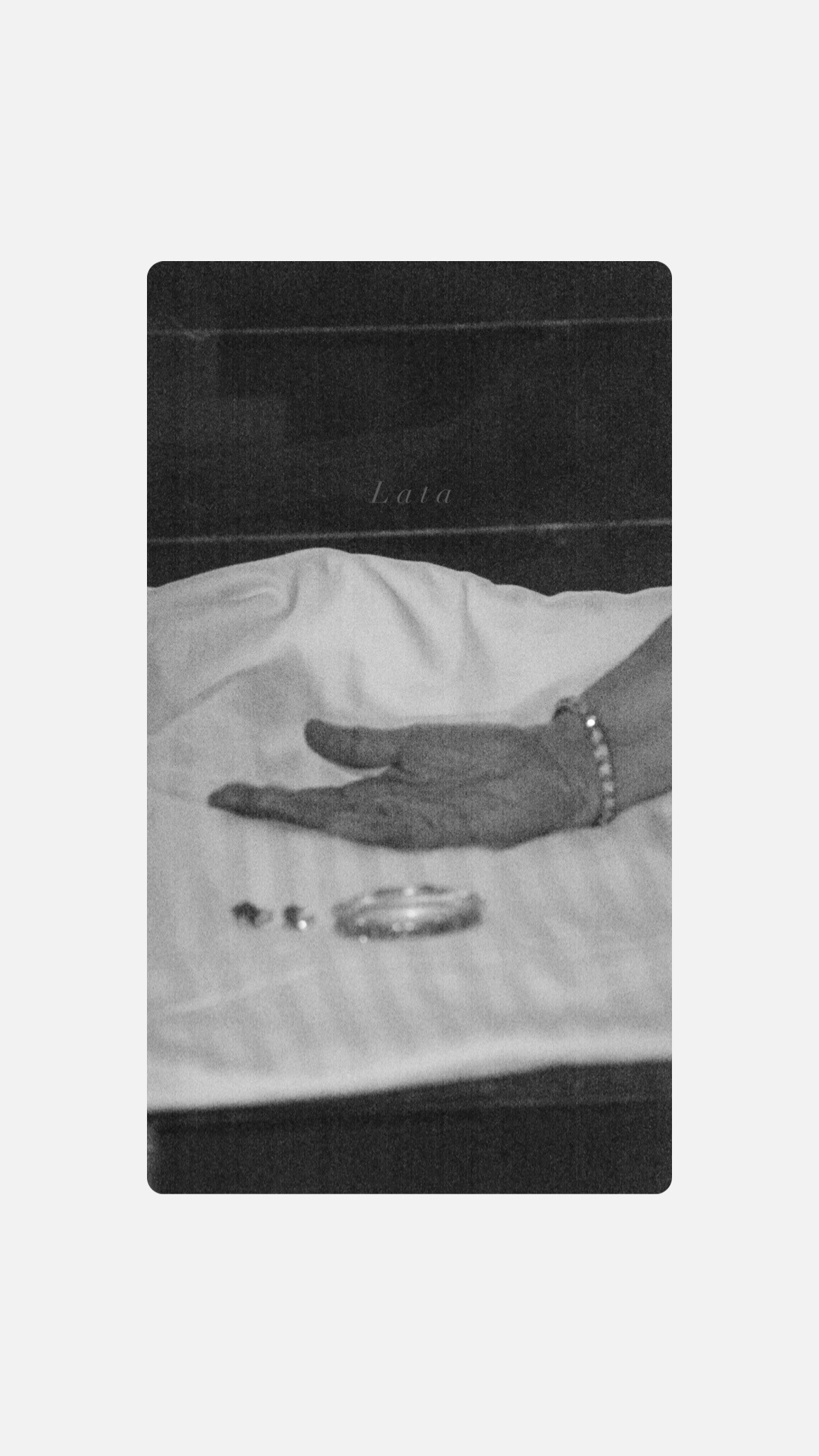

This summer, longing for home, I spend in flats in Bombay/Mumbai. Conducting oral histories, anchored by the medium of jewellery, I speak with the women in my family and our society at large. I began with the people closest to me: my Nani (grandmother), her closest friends, my aunts and great-aunts, charting the city through their eyes and lives. My days are varied. I sometimes cross from one wing of the building to the next, sometimes I travel across Bombay, sometimes I watch my mother sell her own gold and have it melted. I am fortunate—everyone I have asked to speak with, to photograph, has said yes. Sometimes my interviewees are forthcoming, others tight-lipped. They hold my hand, they barely look at me at all.

Jewellery is pervasive in the South Asian home. Pieces can carry multiple kinds of wealth. What’s the rate today? my Nani says, checking the value of gold in the morning. It is gifted by families and lovers and spouses at weddings, births, anniversaries, birthdays. I know this well, I have seen and lived this world. But in a society where jewellery is security, a veritable tie of legal familial connection, what does it mean to take it away? Who owns the family jewels when the family is no longer? For women, what does owning gold mean in a space and time where you were not allowed to own a bank account, or were never permitted to know how to manage one?

Conversations begin generally. I ask about lives, earliest interactions with jewellery and memories. Did you like wearing it? Did you design? What were you gifted? By whom? What are your favourite pieces? Is there one you always wear? Many of these conversations are emotional. We speak of passed spouses and parents and siblings. Love, lust, greed, betrayal—I hear of children who sold away everything of their mother’s, I clutch their hands and tears come to my own eyes. Other family members join in on these conversations, warm and dismissive. It is telling how answers begin to be kept at someone’s entrance. Some women will tell me without my asking, their eyes furious. I hold a momentary worry their anger is directed at me––but then I will be force fed a chocolate or some mithai by their own hands. Cold coffee? Pakora? What will you have? No you cannot sit empty, you must eat. They pause their speeches to make sure I have eaten. Although we often find ourselves near tears, there is much laughter.

I keep a secret question on my lips. But there is a fear in me: I am afraid of asking something crooked. It is on the tip of my tongue, I want to say it desperately: tell me, what has made you angry? Where is this cynicism coming from? What have you not told me? I hear a scoff and a little comment; I hesitate to read between the lines. Do I ask these women I love so dearly—have you ever been forced to give up your jewellery for the sake of the family? And you have done it, haven’t you? What else have you been made to abandon? Who have you had to forget? But I don’t ask. I hear later, in little confessions of relatives.

I used to order my husband before he died, my aunt tells me, sign a contract for our next life and marriage, yes you must do it, because you’re not getting rid of me that easily! She hits her palms together. I hold my Badhi Massi’s hand, I hear my mother’s voice in my mind, I phrase my sentences as I have seen her speak hers. We slip between languages. They celebrated my birthday with me, they open their homes to me. I have no easy answers to the questions I posed but neither am I collecting “correct” responses. I seek only to remember and record––make indelible these voices––before we live in futures without them.